Opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu takes on President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Sunday’s presidential election run-off.

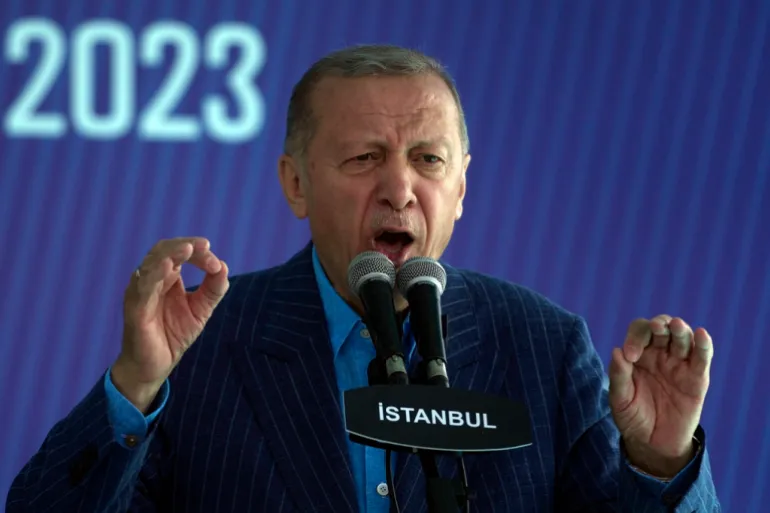

Incumbent Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu have rallied their supporters on the final day of campaigning before Sunday’s decisive presidential election run-off.

The two candidates are aiming to attract some 8 million voters who did not go to the polls in the first round.

A first round of voting on May 14 showed Erdogan with a lead over the opposition’s Kemal Kilicdaroglu, and Erdogan’s AK Party and its allies secured a parliamentary majority in the initial vote.

Erdogan paid homage to his conservative predecessor with a visit to Istanbul’s Adnan Menderes mausoleum on Saturday, to rally his conservative base.

Menderes was tried and hanged one year after the military staged a coup in 1960 to put Turkey back on a more secular course. Erdogan survived a putsch attempt against his own Islamic-rooted government in 2016.

“The era of coups and juntas is over,” the 69-year-old declared after laying a wreath at his mentor’s tomb.

“I once again call on you to go to the ballot boxes. Tomorrow is a special day for us all.”

Erdogan told his followers in January that he wanted to continue Menderes’s fight for religious rights and nationalist causes in the officially secular but overwhelmingly Muslim republic of 85 million people.

Erdogan beat Kilicdaroglu by nearly five percentage points in the first round of voting.

But Erdogan’s failure to top the 50-percent threshold set up Turkey’s first run-off on Sunday and underscored the gradual ebbing of his support. Erdogan, who has led the country for 20 years, is still seen as the frontrunner. Recent opinion polls suggest a close race.

Media reporting from Ankara, said Erdogan’s message has not changed significantly from the first round of the election.

“He was making a promise to make the next century the century of Turkey. He told voters that he would continue the mega project and enhance the defence industry in the country. He was promising a more powerful and assertive Turkey in the international arena,” he said.

Kilicdaroglu, who is heading up an opposition coalition of conservatives, secular parties and nationalists, ended his campaign with a speech at the “Family Support Insurance Meeting” in the capital, Ankara.

Kilicdaroglu has focused on more immediate issues as he tries to come up from behind. In an attempt to win over nationalist voters, the opposition challenger has promised to expel Syrian refugees.

“To attract the nationalist vote, Kilicdaroglu has focused on anti-refugee sentiments in the country and he was promising to send millions of Syrian, Afghan, and Pakistani refugees back to their countries. For now, the opposition is trying to appeal to nationalists,”

On Friday, Kilicdaroglu used a late-night TV interview to accuse Erdogan’s government of unfairly blocking his mass text messages to voters.

“They are afraid of us,” the 74-year-old former civil servant said.

He repeated the same claim on Saturday.

“I can’t send a text message to reporters to announce our campaign program. Telecommunication companies are preventing me from sending text messages to journalists. I’m under a total blackout. We can’t even hold an election in Turkey. This man [Erdogan] is a coward, he is a coward,” he said.

Observers have said Turkey’s votes are free of meddling on election days – but unfair because the odds are stacked against the opposition in advance.

“These were competitive but still limited elections,” the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) election observer mission’s chief Michael Georg Link said after the first round.

“The criminalisation of some political forces … prevented full political pluralism and impeded individuals’ rights to run in the elections,” Link said.

Erdogan’s consolidation of power included a near-complete monopolization of the media by the government and its business allies.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) estimated that Erdogan received 60 times as much airtime on the TRT Haber state broadcaster as Kilicdaroglu in April.

“They have taken over all the institutions,” Kilicdaroglu said in his television interview.

Many issues have turned voters for or against Erdogan: While his first decade in power was marked by strong economic growth and warm relations with Western powers, his second began with a corruption scandal and soon descended into a political crackdown and years of economic turmoil that erased many of the early gains.

Another issue that has taken centre-stage in the lead-up to the elections has been the state of the economy, the growing alarm about the fate of Turkey’s beleaguered lira and the stability of its banks.

Erdogan forced the central bank to follow through on his unconventional theory that lower interest rates bring down inflation, but Turkey’s annual inflation rate touched 85 percent last year while the lira entered a brief freefall.

Economists feel that Erdogan’s government will need to reverse course and sharply raise rates or stop supporting the lira if it wants to avoid a full-fledged crisis after the vote.