Musa Hasahya Kasera has so many children he can’t remember most of their names.

The Ugandan villager is struggling to provide for his vast family, which he says includes 12 wives, 102 children and 578 grandchildren and now feels enough is enough.

“At first it was a joke, … but now this has its problems,” the 68-year-old said at his homestead in the village of Bugisa in Butaleja district, a remote rural area of eastern Uganda.

“With my health failing and merely two acres [0.8 hectares] of land for such a huge family, two of my wives left because I could not afford the basics like food, education, clothing,” he said.

Hasahya, who is currently unemployed, has become something of a tourist attraction. He said his wives now take birth control to stop the family from expanding further.

“My wives are on contraceptives, but I am not. I don’t expect to have more children because I have learned from my irresponsible act of producing so many children who I can’t look after.”

Hasahya’s brood lives largely in a dilapidated house, its corrugated iron roof rusting away, or in about two dozen grass-thatched mud huts nearby.

He married his first wife in 1972 at a traditional ceremony when they were both about 17, and his first child Sandra Nabwire was born a year later.

“Because we were born only two of us, I was advised by my brother, relatives and friends to marry many wives to produce many children to expand our family heritage,” Hasahya said.

Attracted by his status then as a cattle trader and butcher, Hasahya said villagers would offer their daughters’ hands in marriage, even some below the age of 18.

Child marriage was banned in Uganda in 1995. Polygamy is allowed in the East African country according to certain religious traditions.

Hasahya’s 102 children range in age from 10 to 50 while his youngest wife is about 35.

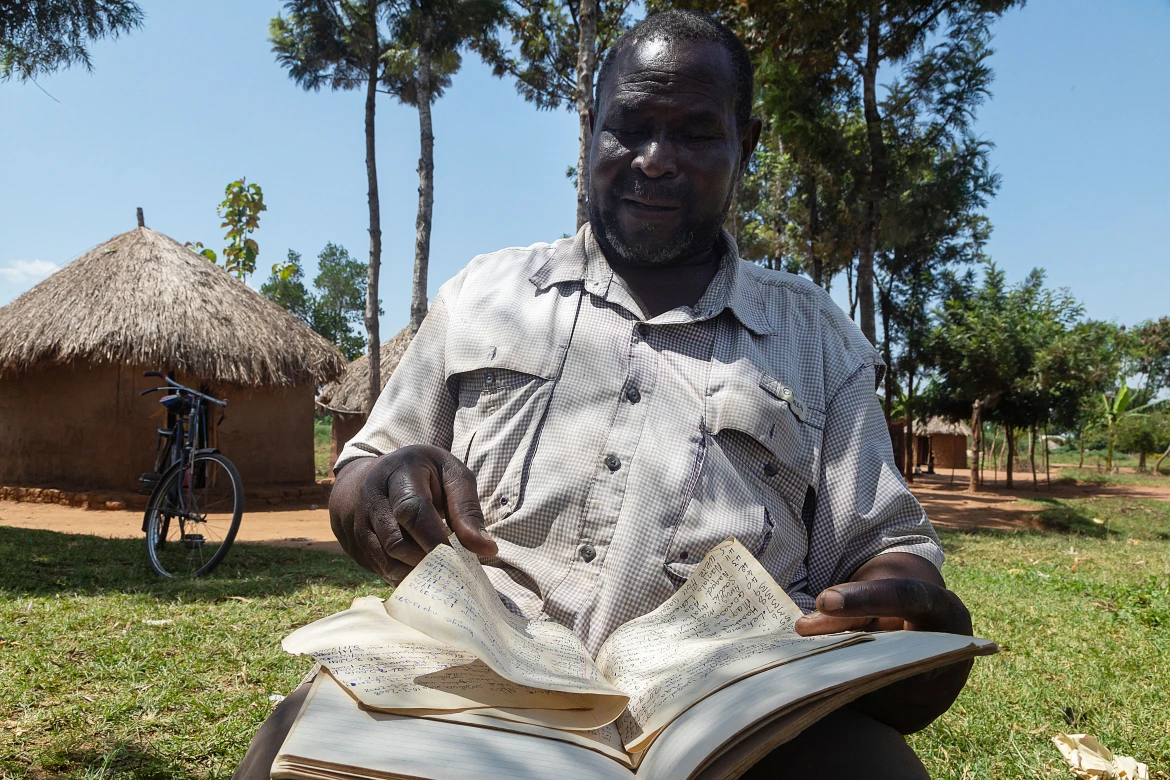

“The challenge is I can only remember the name of my first and the last born, but some of the children, I can’t recall their names,” he said as he rummaged through piles of old notebooks looking for details about their births.

“It’s the mothers who help me identify them.”

But Hasahya can’t even recall the names of some of his wives and has to consult one of his sons, Shaban Magino, a 30-year-old schoolteacher who helps run the family’s affairs and is one of the few to have received an education.

To resolve disputes in such a large family, Hasahya says, they have monthly meetings.

A local official who oversees Bugisa, a village of about 4,000 people, said that despite the challenges, Hasahya has “brought up his children very well” and there has been no fighting, for example.

Bugisa’s residents are largely peasants who raise cattle and are involved in small-scale farming of crops such as rice, cassava and coffee.

Many members of Hasahya’s family try to earn money or food by doing chores for their neighbours, or they spend their days fetching firewood and water, often travelling long distances on foot.

Those at home sit around the grounds, some women weaving mats or plaiting hair, while the men play cards under the shelter of a tree.

When the midday meal of boiled cassava is ready, Hasahya saunters out of the hut where he spends most of his day and calls out in a commanding voice for the family to line up to eat.

“But the food is barely enough,” says Hasahya’s third wife, Zabina. “We are forced to feed the children once or, on a good day, twice.”

She said if she had known he had other wives, she would not have agreed to marry him.

“Even when I came and resigned myself to my fate, … he brought the fourth, fifth until he reached 12,” she said.

Two of his wives have left Hasahya, and another three now live in another town about 2km (1.2 miles) away because of the overcrowding at the homestead.

When asked why he thought more of his wives did not abandon him, Hasahya declared: “They all love me. You see, they are happy!”